The Affictitious

Historiaster

affictitious {adj, Obs.} [f. L. affictīci-us annexed, f. affict– ppl. stem of affing-ĕre to add to by inventing: see -itious.] Feigned or counterfeit.

historiaster {noun, rare} [f. L. historia history + -aster.] A petty or contemptible historian.

A Scholarly Analysis of The Affictitious Historiaster

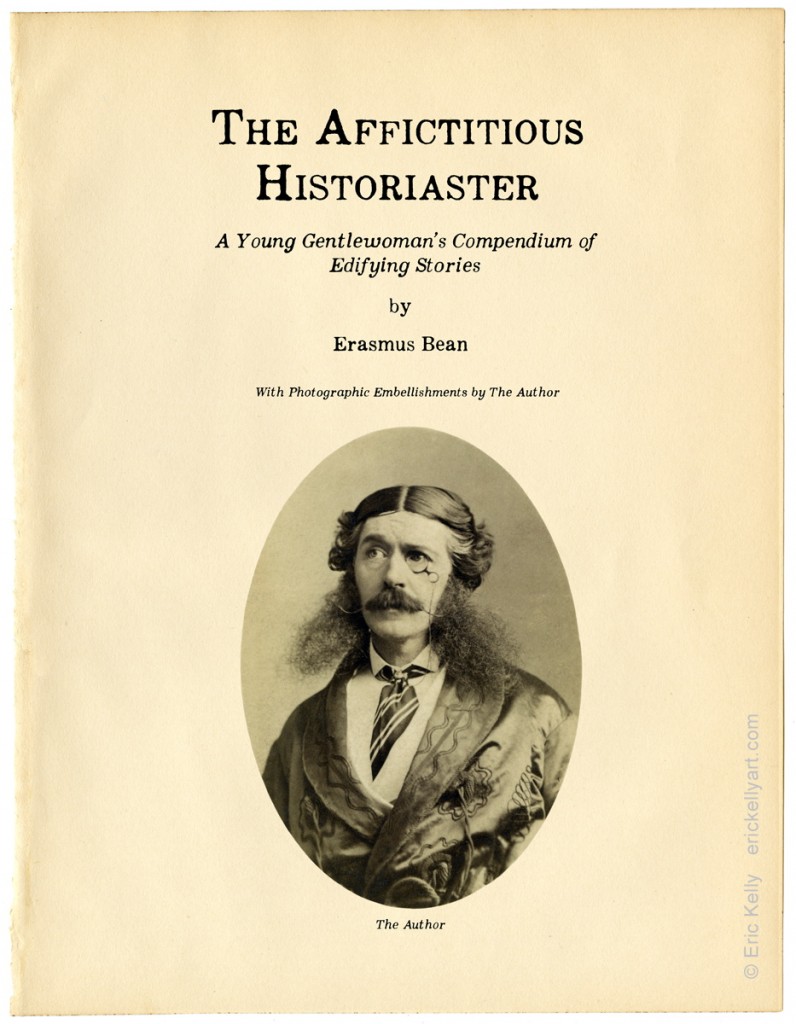

In the summer of 1899, a writer by the name of Erasmus Bean published a limited edition of his book, The Affictitious Historiaster, subtitled A Young Gentlewoman’s Compendium of Edifying Stories. Erasmus Bean is almost certainly a pseudonym, and the work’s first and only edition appears to have been largely financed by the author, as the publishing house was (rightfully, as it turned out) skeptical of its mass appeal. The work belonged to the genre, then popular, of stories written for the benefit of a youthful audience, in which various life lessons are illuminated by the travails of the characters, who often find themselves in difficult yet avoidable circumstances as a result of their faulty moral choices. It met with little notice at the time, with the few critical reviews being overwhelmingly negative. The critic of the Manchester Guardian described it as “utter rubbish, unfit even for the library at a bordello”, while the Daily Mail’s reviewer noted that while its title suggested that its intended audience was young ladies of good breeding, it was in fact “barely suitable for the most rough and tumble street urchin of the lowest order.” Unsurprisingly, the book appears to have sold quite poorly.

Bean’s work would otherwise have been relegated to historical obscurity, had not fate shortly thereafter set a course that collided with no less a personage than HRH Alexandra, Princess of Wales. It is not known if the copy of The Affictitious Historiaster in the children’s library at Marlborough House arrived there as a family purchase or as a gift. What is known is that on October 5, 1899, someone (whether it was a governess or HRH herself is not recorded) read aloud from this book to the royal grandchildren, including, presumably, the two future kings of England, then quite young; on October 6, a royal edict was issued by Queen Victoria declaring the book an obscenity, and ordering that all known copies must be surrendered to the authorities for prompt destruction, and that any persons found knowingly harboring a copy of the book would be liable for stiff fines and prison time.

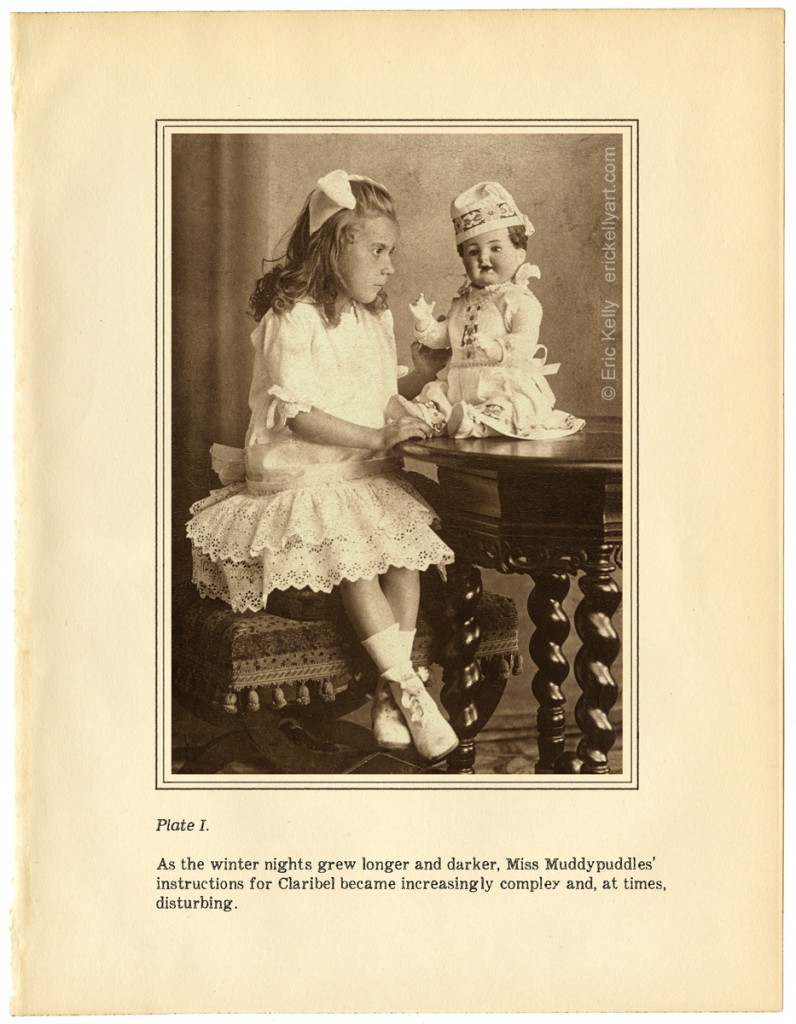

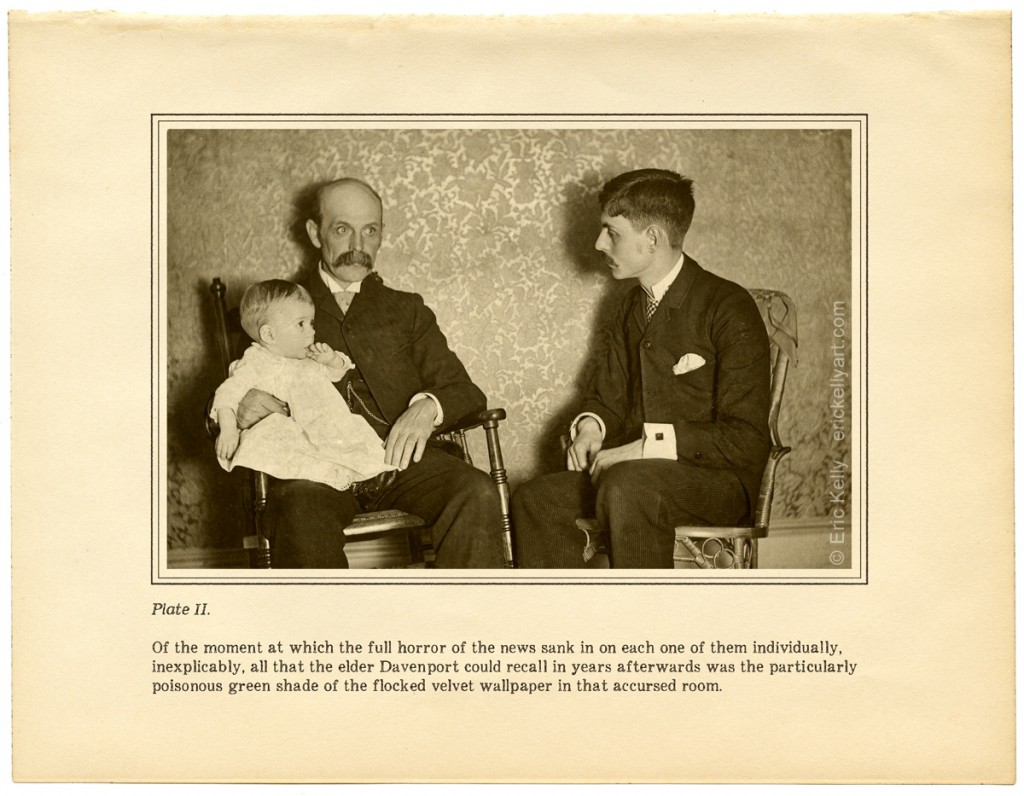

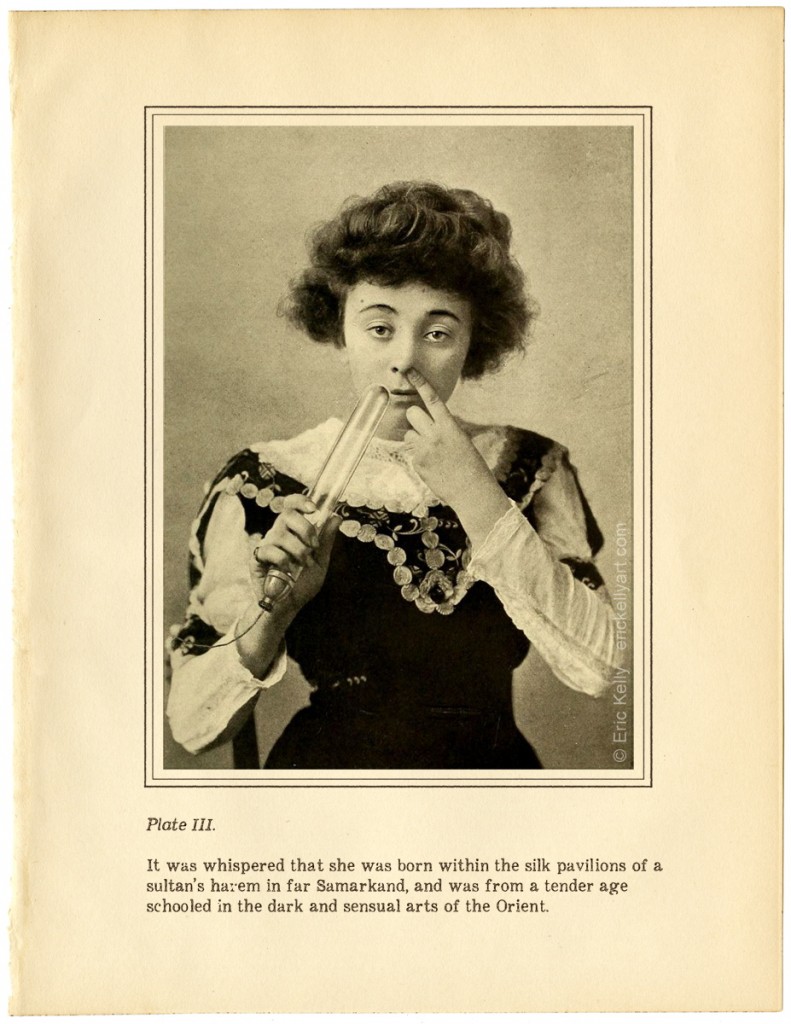

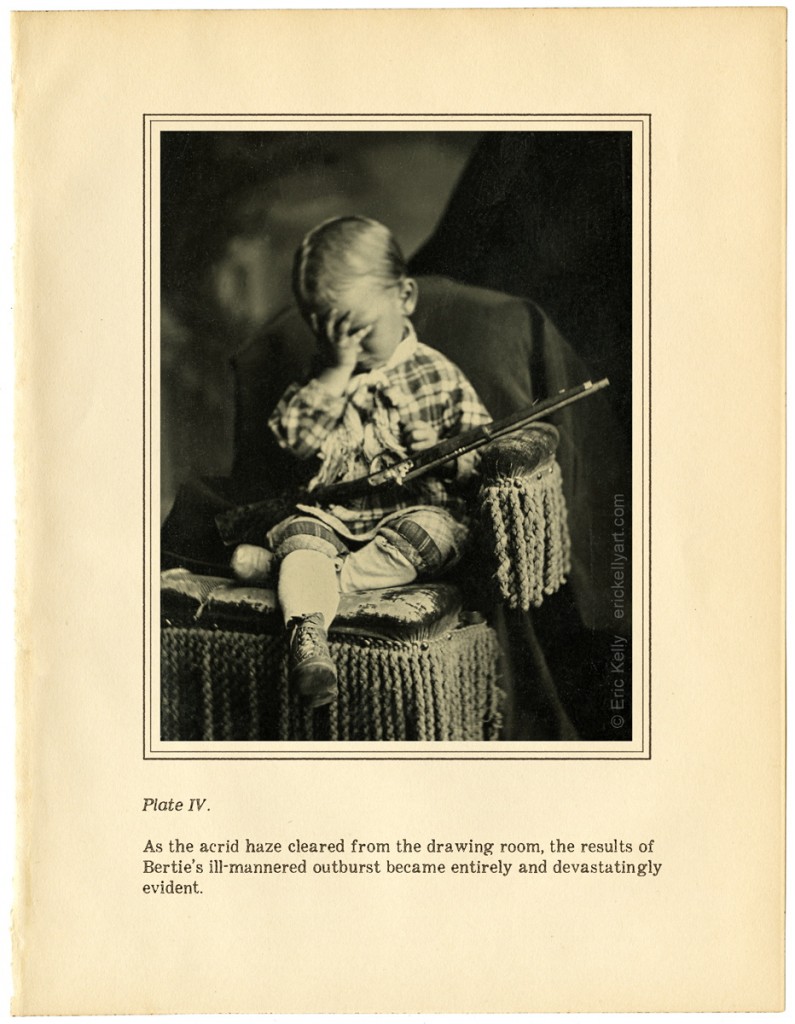

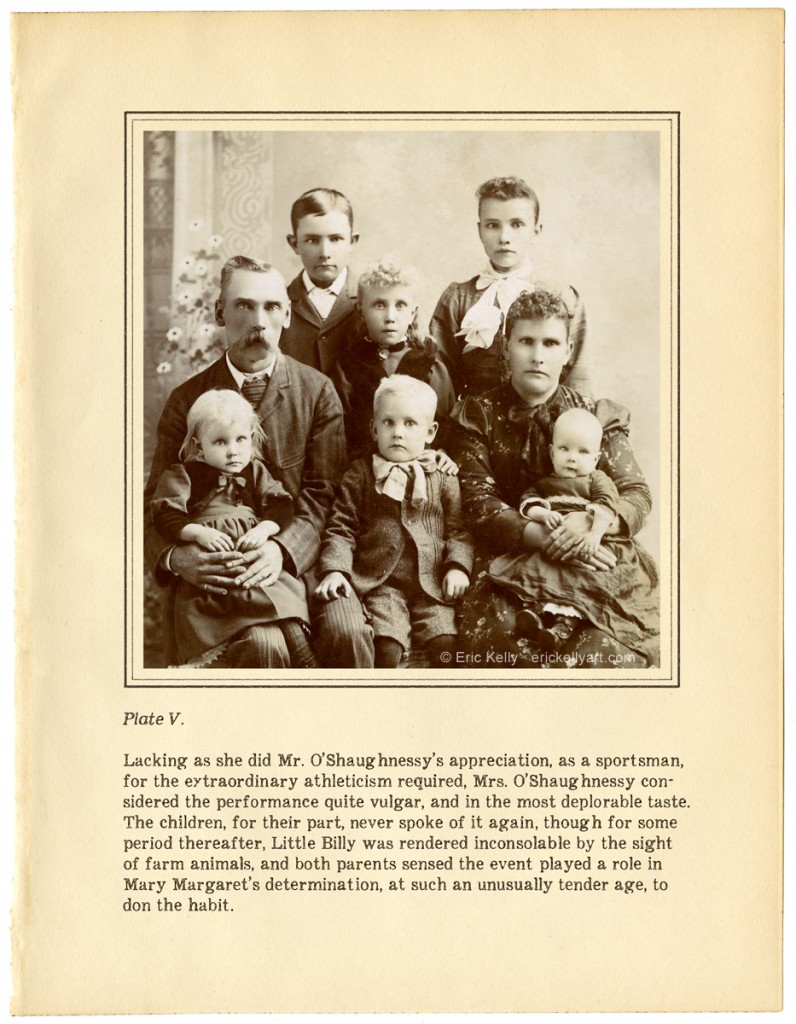

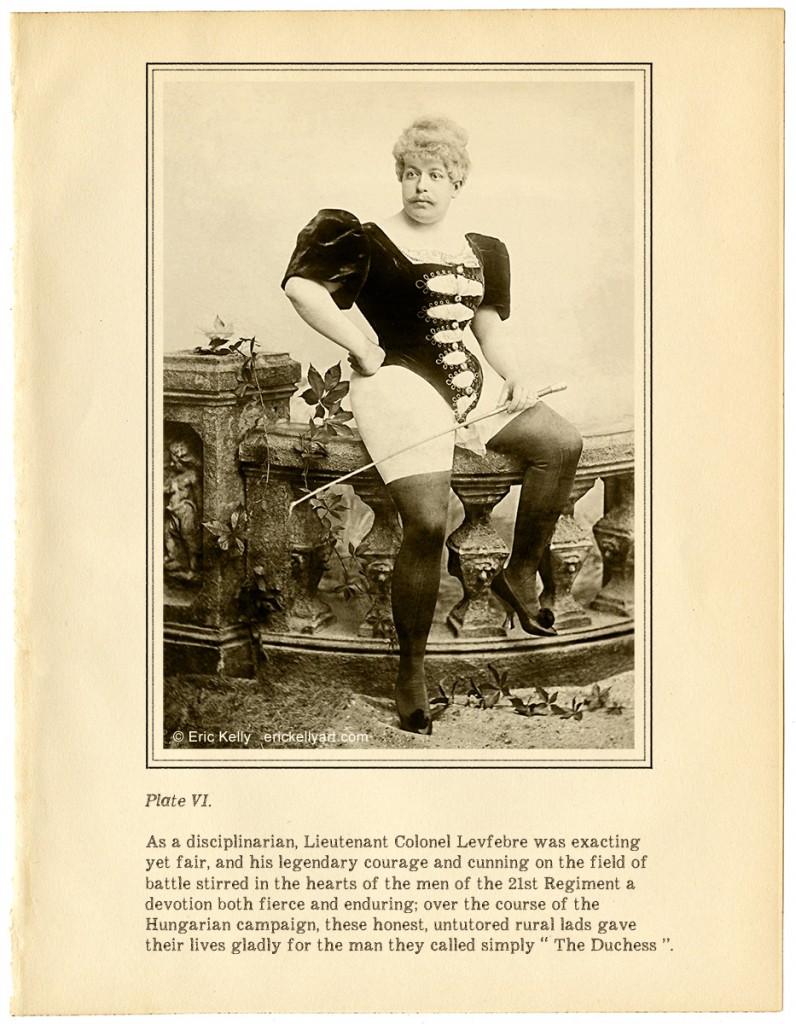

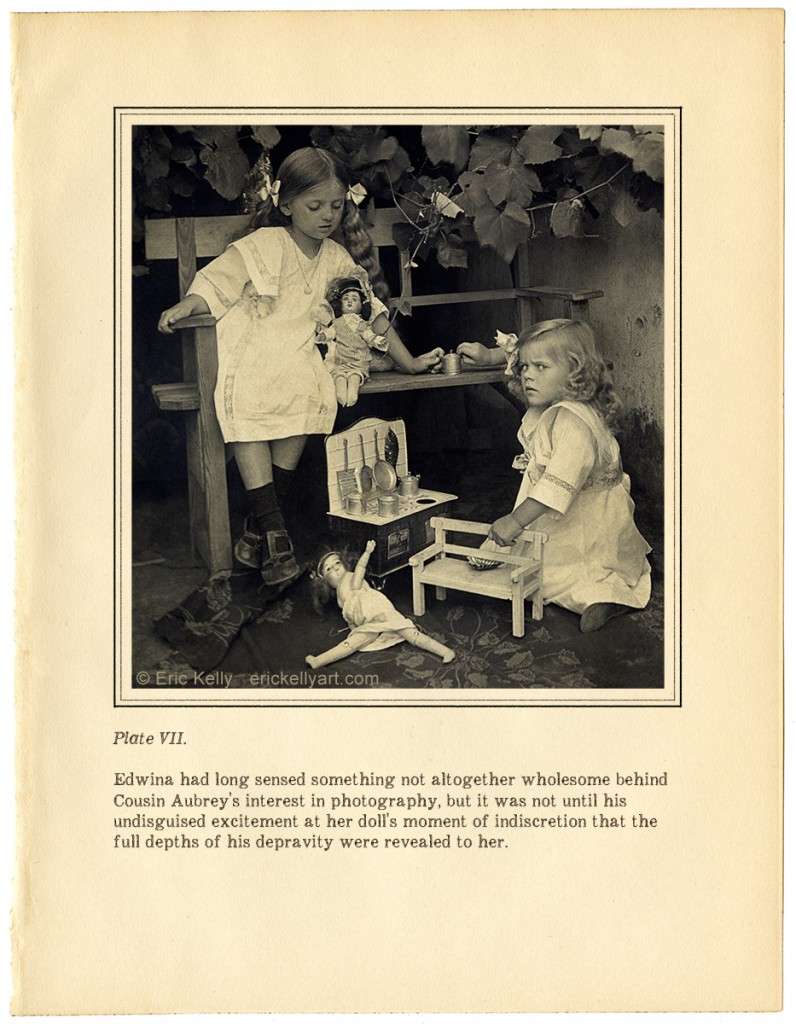

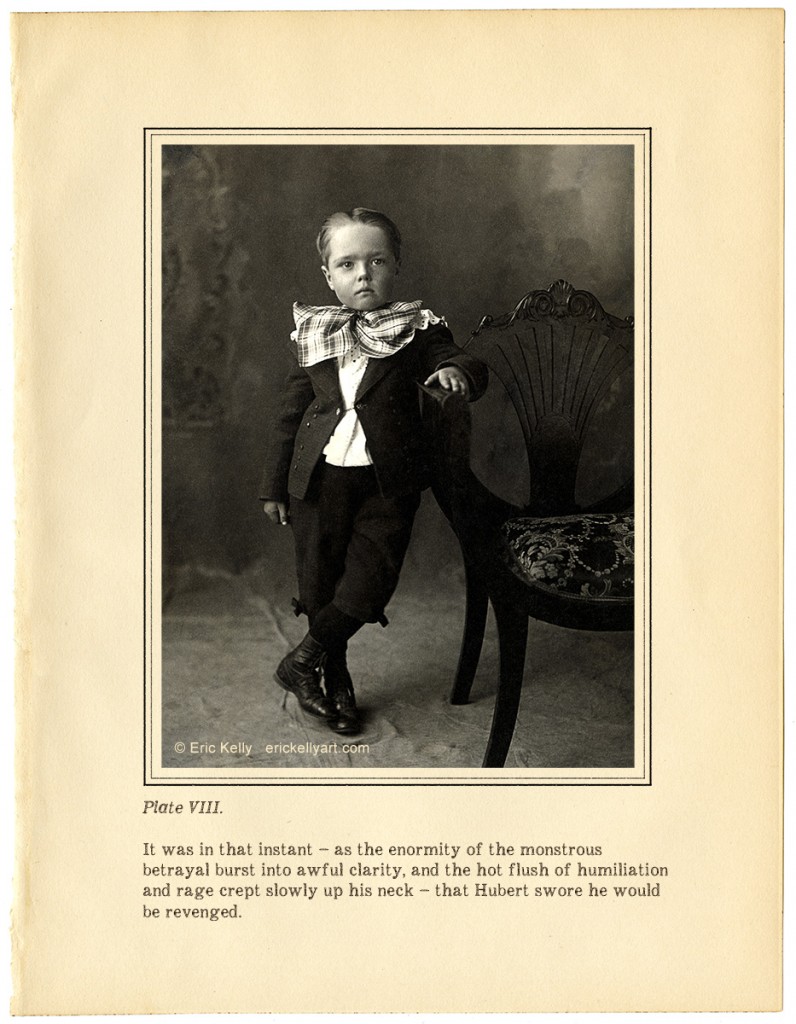

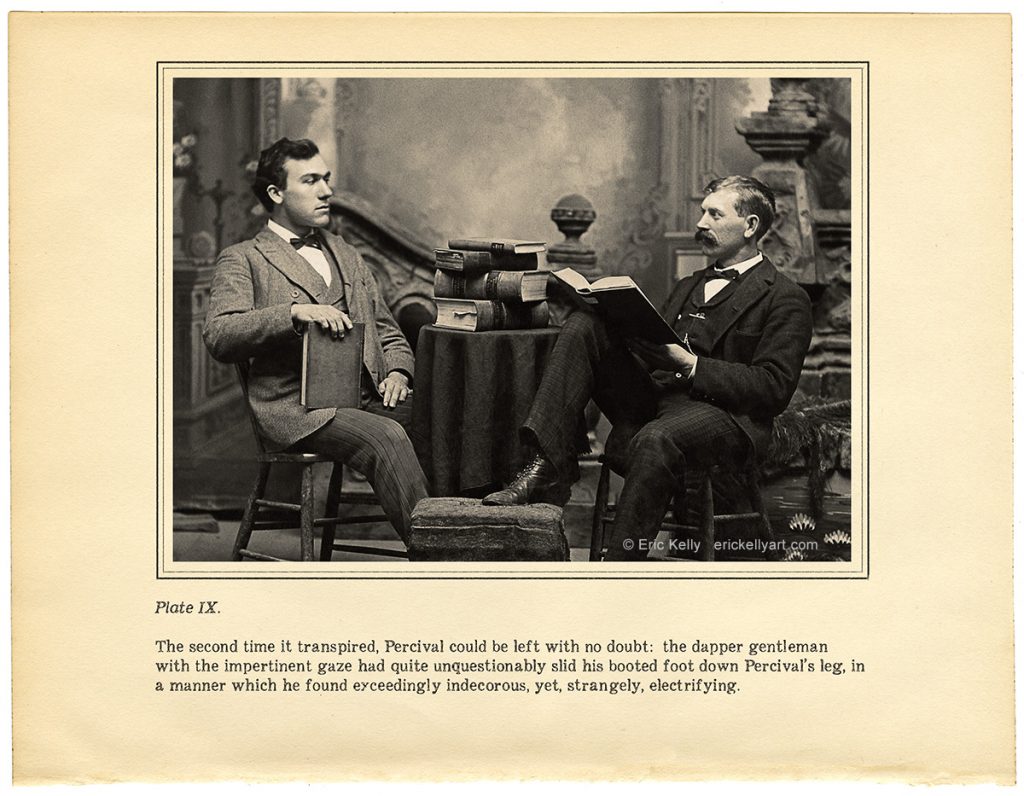

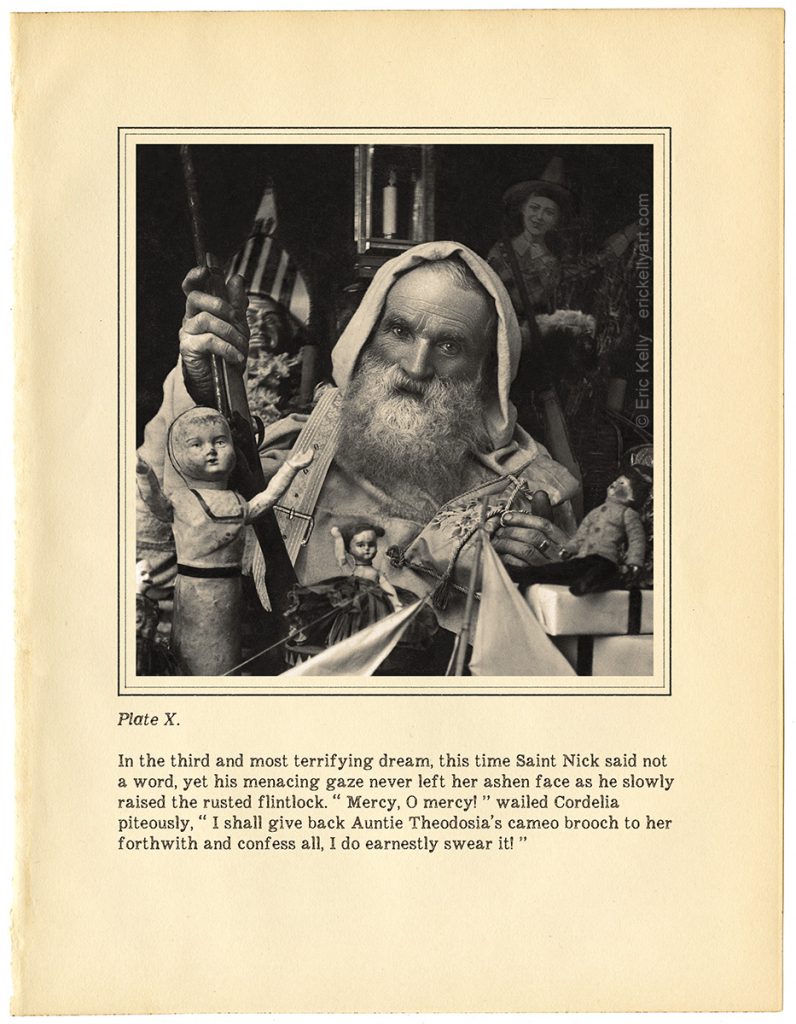

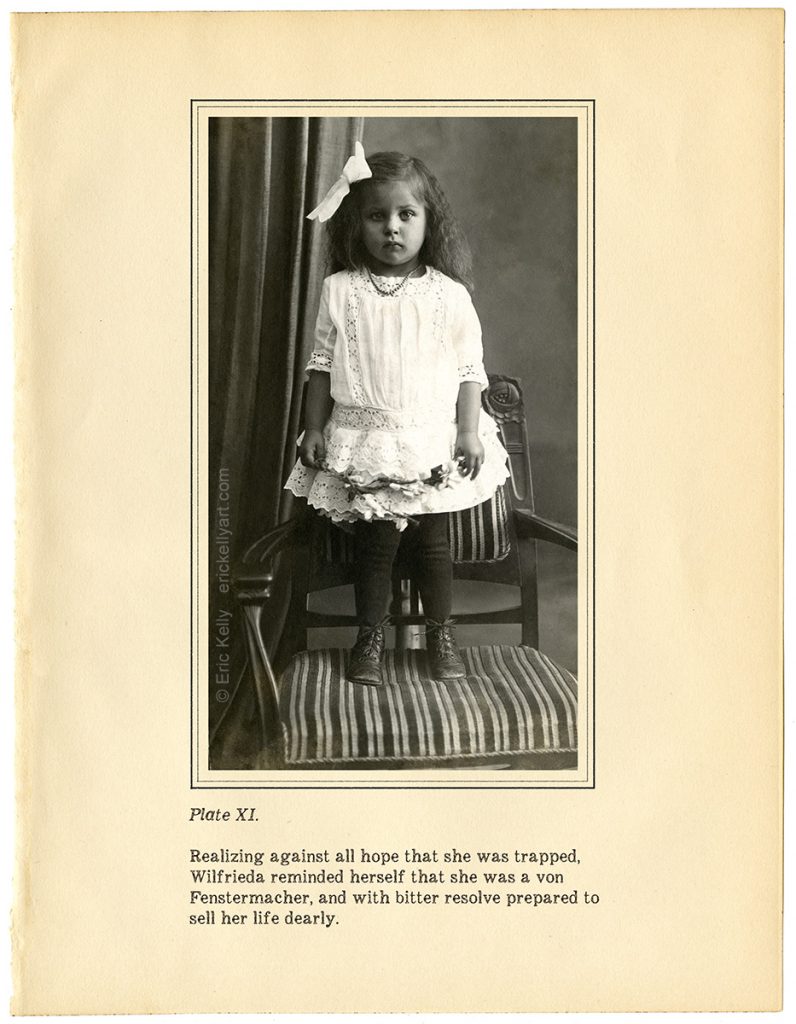

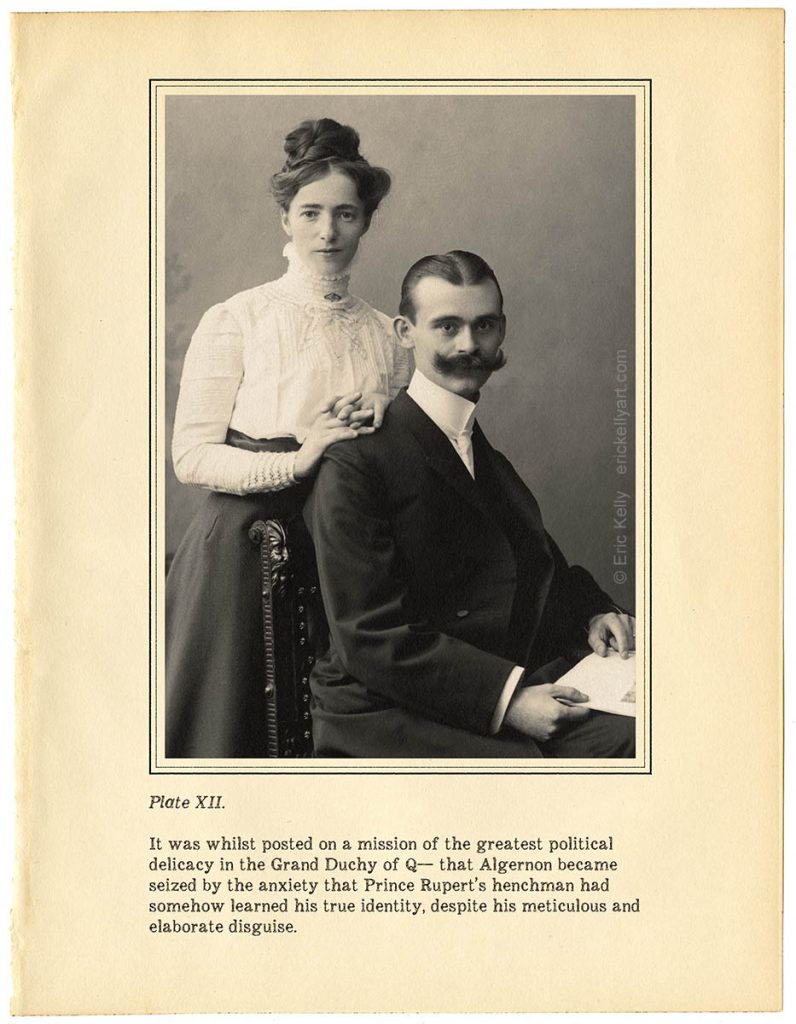

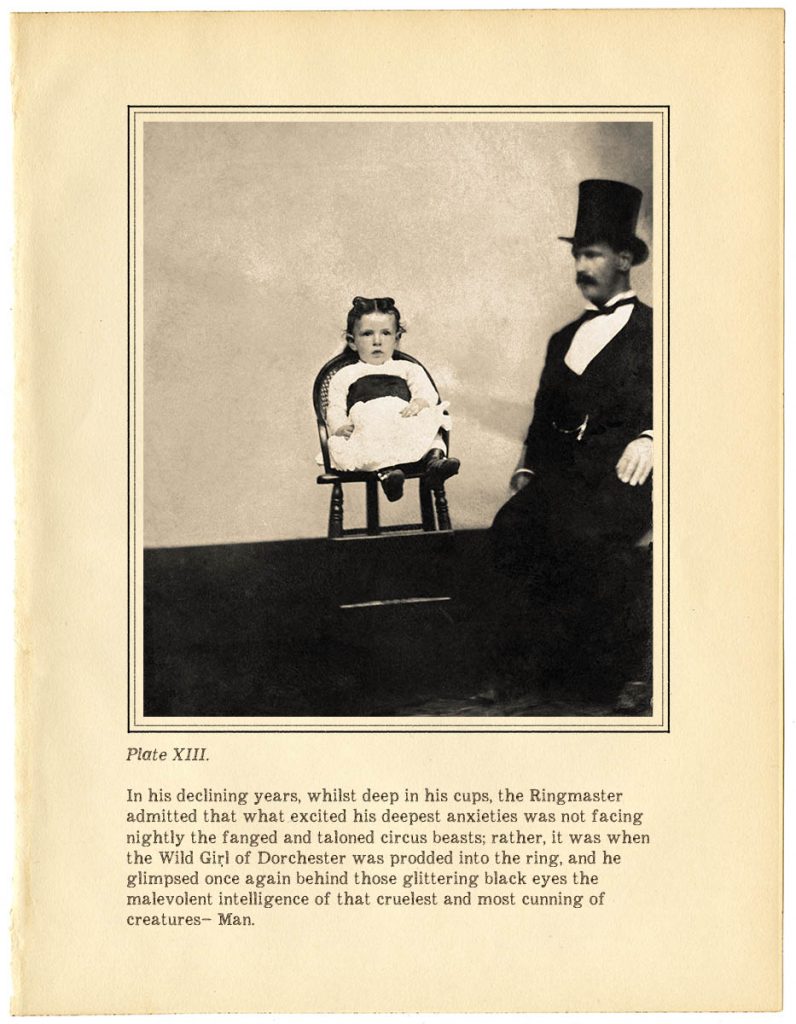

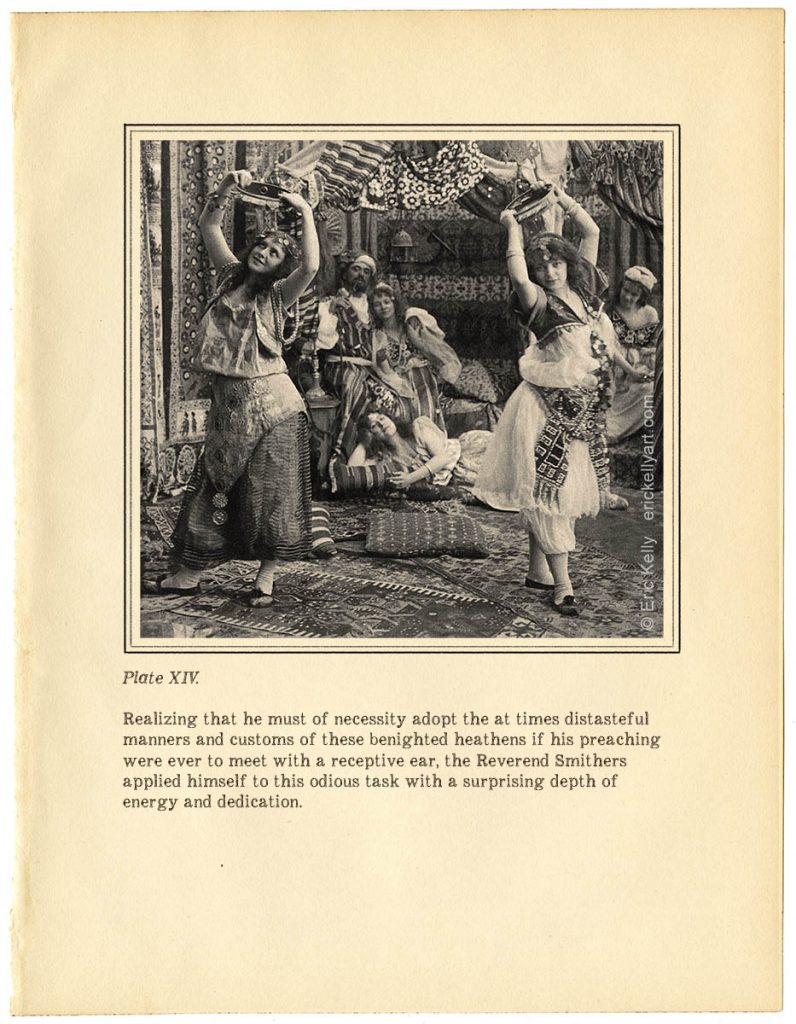

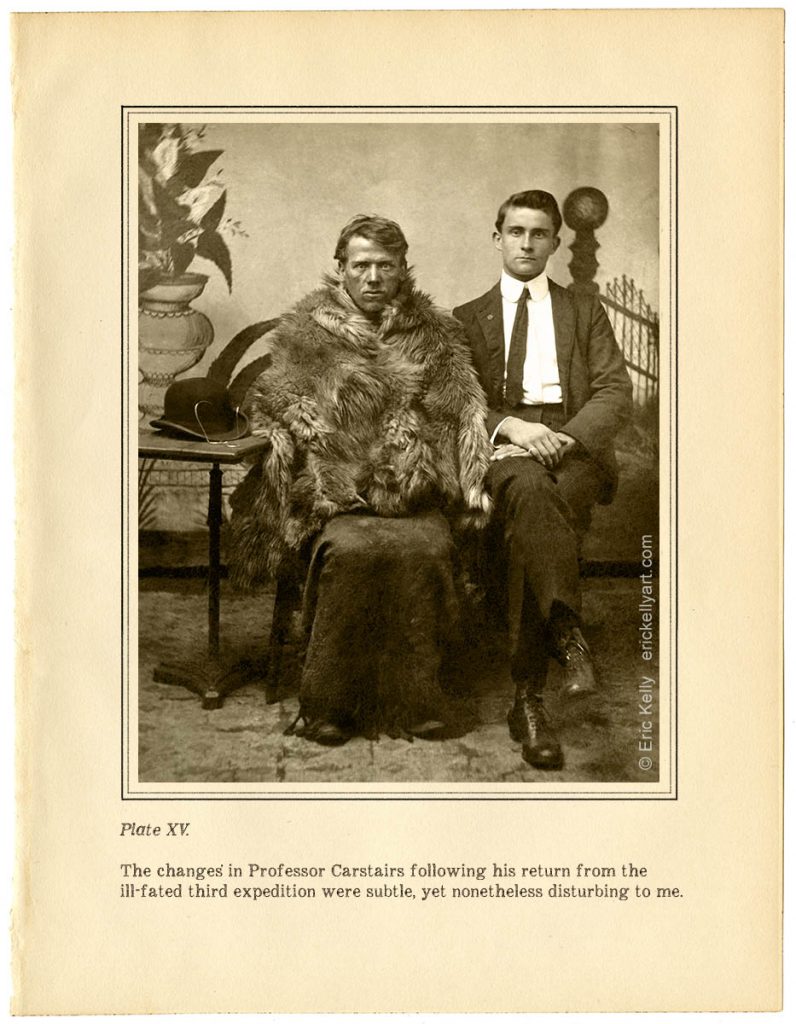

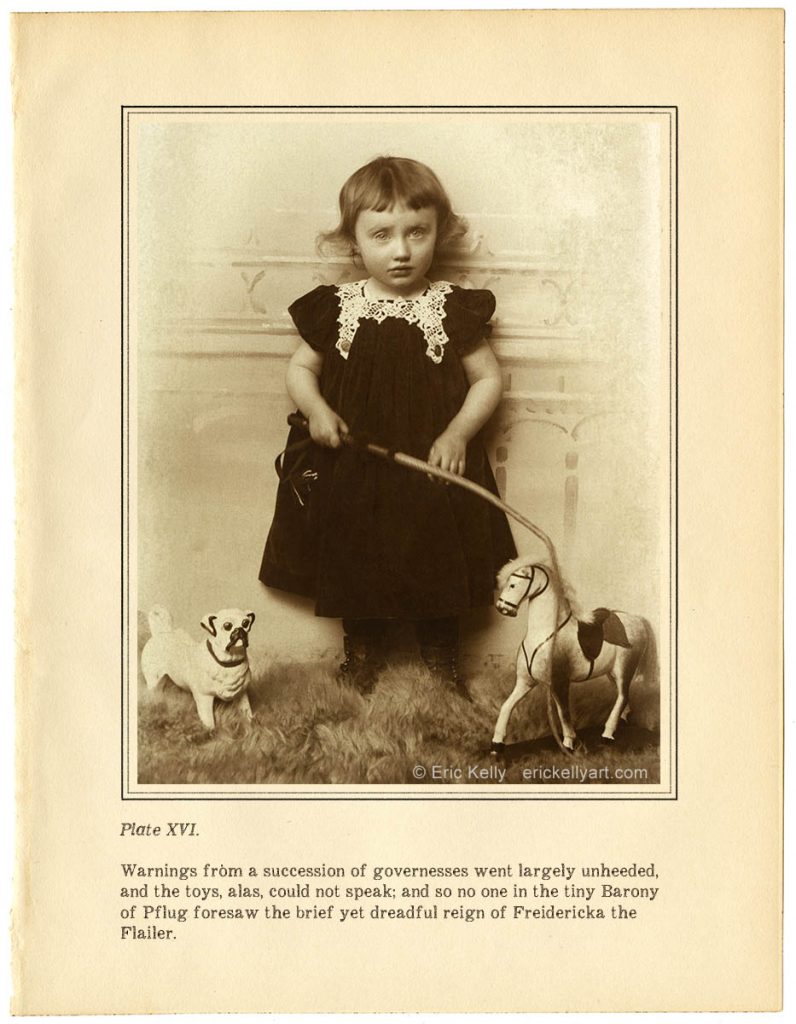

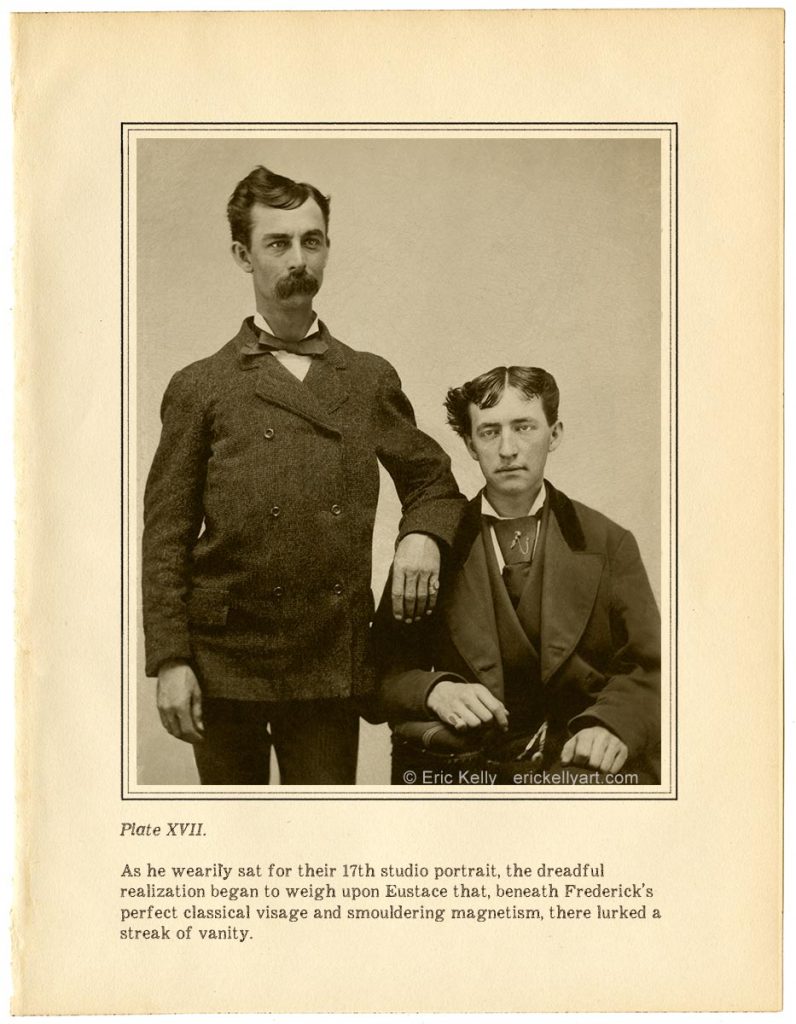

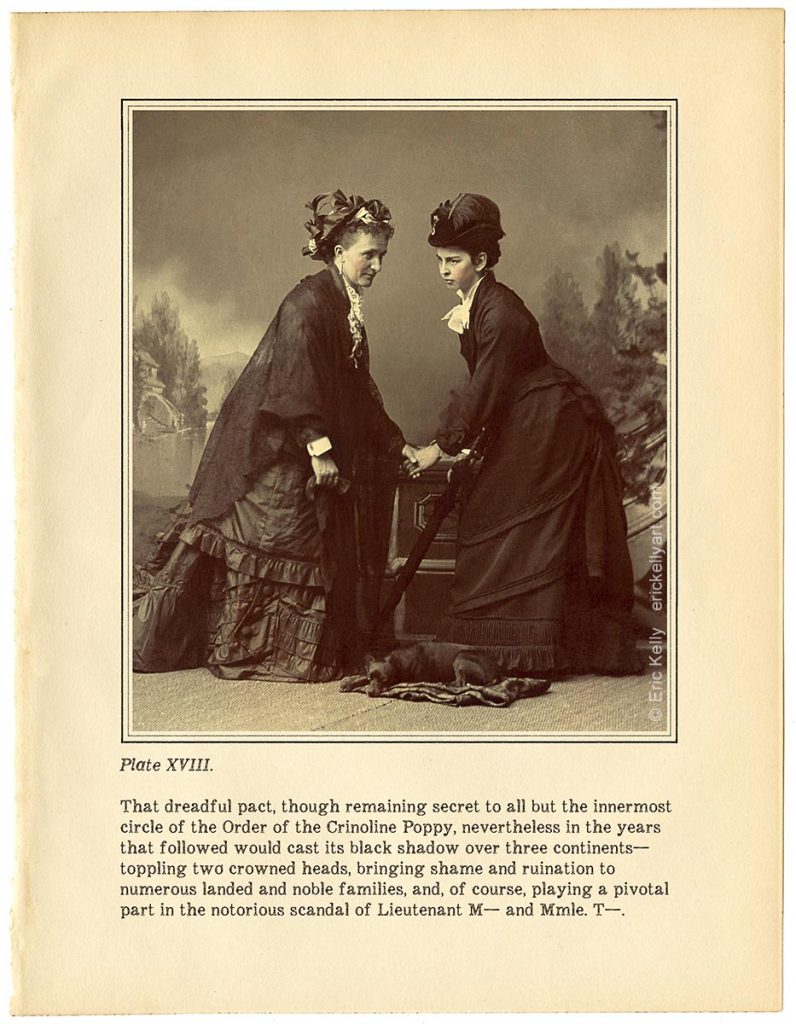

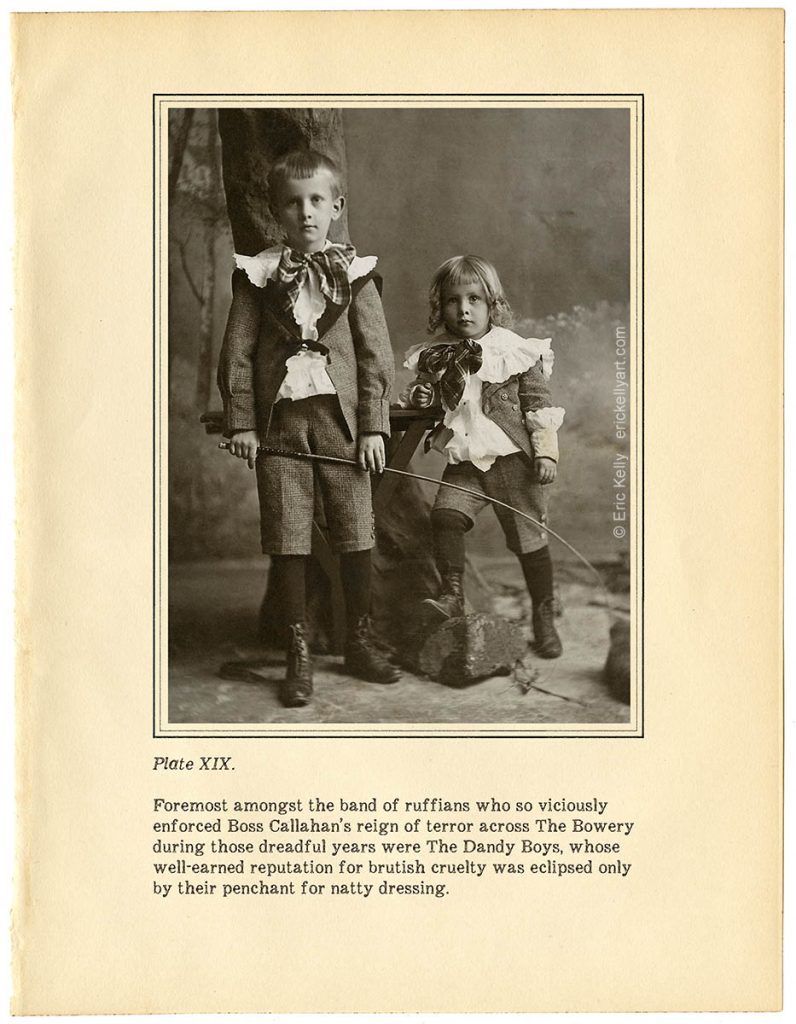

This program of destruction was so effective that today there is only one known surviving copy of the book, and as shall be seen, it is in partial form only. It was found in the estate of one Henry Marple, who in his lifetime served as the beadle of Pratt’s Bottom in the Bromley Rural District. As the beadle, he would have been tasked with carrying out the order to collect and destroy all local copies of the book. We can only wonder why he chose to secrete away this one copy, or, more precisely, its title page and plate illustrations. He carefully removed all the plates and then (presumably) discarded the rest of the book, with the result that we are left to speculate as to the exact content of these stories that were considered so scandalous at the time. The captions on the pictures provide some tantalizing hints, but that is all.

Even with this very redacted remnant, we are struck by the oddness of it, both in terms of some of the implied themes (violence, bestiality, homosexuality, mental illness), but also by the nature of the illustrations. In an era when most illustrations consisted of line drawings and engravings, in The Affictitious Historiaster, each plate is a carefully reproduced photograph. A closer examination of these photographs reveals a wide range of styles, historical eras, and frankly, technical quality, suggesting that rather than being the work of the author himself, as claimed on the title page, these photographs were gathered from diverse sources. It has been even suggested that the pictures may have pre-dated the stories, which, in this scenario, were inspired by the pictures themselves. But since we no longer have access to the text, this is only speculation.

Of possible historical relevance, in 1902 a suit was brought in the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria against one Arthur Frimley-Jones by a previous employer, a family that had provided him room and board in exchange for tutoring services for their young children. The suit alleged Frimley-Jones had secretly pilfered numerous family photos from their private albums and that these photos were then “illicitly published as illustrations in a book of vulgar and lascivious fiction of a most base nature.” The suit was later joined by two other families in whose households Frimley-Jones had held a similar office. The action was eventually dismissed, Frimley-Jones getting off with an admonition and a 35 shilling fine. Because no specific details are provided in the court documents of the exact nature of the photographs or the book of fiction, no definitive link between Frimley-Jones and Bean can be made.

An alternate theory to explain the documents has been advanced, namely, that it is all an elaborate hoax. According to this theory, Erasmus Bean was nothing more than a cover for an unscrupulous antiquarian seeking to increase the resale value of his photo collection by conferring upon it the sheen of historic significance. Advocates of this theory point to certain inconsistencies of language in the picture captions, as well as to specific visual anachronisms of dress and photographic conventions that call into question whether all of the pictures pre-dated the supposed publication date. This theory has however been largely discredited.

We are left therefore with the work itself, to be judged on the basis of its artistic and literary merit – though, as most viewers will quickly agree, this is a dubious proposition indeed. To a modern person, the pictures and captions will no doubt seem quaint and perhaps at times even unintentionally comical. However, it should be remembered that in the context of the era, the moral education of youth was taken quite seriously indeed, and therefore it behooves us deliberately to set aside our 21st century skepticism and sense of irony, in order to fully appreciate these works as they were originally intended.

To Be